Since it’s Valentine’s Day, I thought I’d post a love story. This is a somewhat expanded version of the one that’s in Just Passing Through.

Motorcycle Memories

Chapter Two

France the Fair

by

James Morgan Ayres

We rolled off the ferry from England on a thumping Triumph motorcycle and into the green fields of Normandy on a grey March afternoon. I was in my early twenties, as was my dark eyed girl wrapped warmly around my back. I had bought the sleek silver and blue bike in London, along with a small green tent and a double air mattress and sleeping bag. Carolina came with me from the States. Sweet Carolina. Carolina was a small pretty girl, with long ink black hair, eyes as dark and deep as a cold water well, high Indian cheekbones, leather tough loyalty and a streak of wildness nearly as wide as my own. She came with me for romance, for a desperate need to let go of common sense and find her way to some unknown place where the workaday world lost its meaning and her heart could run free. In me she had found her guide. In her I had found my true companion of the road.

We had spent a month slowly wandering English back roads, easy miles to let the new engine break in, camping in farmyards and fields, sneaking onto castle walls to make love and sleep under stars and sky and dream of knights and maidens. At Stonehenge we eluded the sole custodian and bathed naked in moonlight on grass in the center ring, holding in giggles and laughter and drinking Chianti from a straw covered bottle.

Back in London the mechanic checked the valves, tightened the chain and said the engine was well broken in and we were good to go. I hit the entrance to the A1 with second gear screaming and the rear tire slipping sideways, engine roaring, foot peg dragging, and we were up and away to the Channel, doing “The Ton,” as the English café racers called one hundred miles an hour, a cold rain stinging my face, Carolina warm at my back, tucked in, holding tight and flying low, our course set south for France the Fair.

We blew through Calais, the pull of the road too strong to consider stopping. Long straight roads lined on each side by Napoleon’s plane trees, tires humming on blacktop, a rushing river of wind washing over us, forcing its way through the silk scarf wrapped around my face below the goggles, the grip of the throttle solid in my right hand. Up through the gears and we’re flying faster and faster, vision and perception confined to the narrowing road. “Do it,” Carolina yelled in my ear. “I don’t care. Do it.”

I set the throttle, stood up straight on the pegs let go of the handlebars and let the motor have its head. Carolina stood up behind me, both of us with arms outspread, flying through the green scented air, flying through a dream, hearts full to bursting, tears streaming, trusting to the universe to bring us through. A small bump, a pothole, a tractor pulling onto the road from a field, anything could have brought us down. But nothing did.

We crested a small hill and swooped down into a lush valley spread out around us like a gift from the Gods. Then we sat back in the saddle and I eased off the throttle, both of us thankful and happy and spent, empty, yet filled and complete in a way we couldn’t define.

After that, we idled along for miles, past stone farmhouses, brown and white cows, men walking with hoes over their shoulders, late afternoon sun falling on fields, the light as pale and soft as moonlight on a dark lake.

My Triumph was a model TR-6 with a powerful 650cc engine, set up with a trouble free gas sipping single carburetor and an oversized five gallon tank, which extended my range further than would have been possible with the faster but finicky gas guzzling twin carb Bonneville model. Range was what I wanted, as much as I could get. I knew my place in life was on the never ending road and I didn’t want to be bound by more gas stops than necessary, or bound by much of anything else. Cocked sideways on its kickstand the proud machine called out me, ‘Get on, mount and go, go anywhere, anywhere at all, just go.’ Wherever we stopped small crowds circled, looking long looks, the yearning in their faces as clear as the desire in their questions. “How fast will it go? How far? Where are you going?” And unspoken, “I wish I could come.”

Nothing would have been the same without the Triumph, not the road, not the countryside, not the people we met, not the clean wind, and surely not the girl at my back. Our days, our lives, everything would have been dulled down if we had been contained in a car, a bus or a train. The rearing, leaping, running, half wild animal of a motorcycle was the center of it all and made it all possible, and shaped the hours the bright days and soft nights, and the memories.

Carolina loved the Triumph as much as I did. Its power took her to places she had never been, but had always wanted to go, even if she wasn’t quite sure where those places were. Her fear came up at speed. After the first high speed run and sweeping curve, she dismounted pale and trembling, her hands shaking too much to unzip her leather jacket. I told her I wouldn’t do that again, that I’d go slower.

“No,’ she said. ‘Go faster. Go as fast as you want to go. Go as fast as you can.”

Carolina came to desire the speed. She discovered the secret place that can only be found by going to your fear, a free and easy place where all of life opens before you. We rode fused together, bodies and minds working as one, as we shifted our weight and balanced through turns, dips and rises in the road. The day we spread our arms and let fate take us bound us together more tightly than our love making.

We rode all that day, stopping only once for gas and to gobble a shared sandwich from the ferry. We rode until the sun touched the low horizon, and rode on into the enfolding blue dusk, reluctant to leave the road before getting some unmeasured but urgent distance deeper into the heart of the country. The moon rose full and brilliant and I turned the headlight off and we rode on through the night, washed in pure golden moonlight.

Finally, tired and saddle sore, we pitched our tent by starlight on mattress thick grass next to a café in a crossroads village. The café was open but we had missed dinner. We pleaded starvation and Mssr. Bayard, the proprietor, a red faced good natured man, provided an omelet and a carafe of red wine, both of which disappeared in an instant. Afterwards, we drank cognac with the locals, country people in thick clothing with hands that can only be gotten by years of hard outdoor work.

The café closed and we made our slightly drunken way to our green tent. There we made love, first heated then playful then tender, a celebration and close to the perfect day. Afterwards we lay entangled and talked down the moon, watching through the open flap as it slowly settled into trees. Through night hours we listened to the scuttlings of small creatures out and about their business and talked about where that day had taken us. Finally we fell into a deep sleep, our first night in fair France.

The lush grass was wet with dew when we crawled out of our little home and into the pearl colored morning. We stumbled into the café in search of breakfast. The eggs and bacon we had in mind were not to be. But the fresh baked bread, and the butter – oh my God. This, was how bread and butter tasted? My life had been wasted until now. How was it possible that I had lived so many years in such poverty of experience that I have never known the true nature of simple bread and butter? We ate like we had been lost in the forest for days, baguettes slathered thick with rich butter. Following the example of the locals we dunked our bread in bowls of warm creamy café au lait. Mssr. Bayard watched us with an indulgent smile and brought more bread and another crock of butter.

We went to break camp and found our tent damp and heavy with dew and bearing no exterior trace of the night before. How marvelous. What magic. That a small roll of fabric could become a private space, a bedroom, a place of warmth and laughter and love. We rolled our home into a bundle and strapped it on the Triumph’s back, memories of the night safe inside.

We rode easy and slow through the morning, idling down country roads, always south, deeper and ever deeper into France. In late afternoon when the Triumph’s big tank was nearly empty I pulled in for gas at a single pump in front of a one room stone fronted store. Two older men sat on a bench nearby and watched me fill the tank. After I paid for the gas one of the men got up and leaning on his cane walked to us. He wore a frayed tweed jacket with a small ribbon in the lapel, a blue beret and a grey shirt with a black tie. Marcel Devereux introduced himself formally and asked us if we were English and why we had come to France.

I said we were Americans and that I had grown up hearing stories about La Belle France from my father and uncle, both of whom had been wounded at Normandy, and that I was now on French soil for the first time.

Marcel grabbed me in a strong embrace, kissed me on both cheeks and said, “ Mon amis. Your family has bled for France. You will forever be a friend of France.”

Marcel had fought with the Resistance in War II. The ribbon in his lapel was the Croix de Guerre. He pulled up one pant leg to show his wounds, puckered scars the size of silver dollars on each side of his calf. He had been hit during a roadside ambush a few days after D-Day. He never once used the word ‘German.’ He always said “Le Boche,” and spit when he did so, as if the word itself left a bitter taste. War memories, we learned, were raw and fresh for many Frenchmen in 1968.

I didn’t tell him that my uncle had been damaged beyond hope of healing and was a barely functioning alcoholic with one eye and a plate in his head, or that he had fought across France and Germany and that his unit was the first into Dachau, or that he told three am drunken stories about what he saw at Dachau and how he and others had “Lined up the Nazis and shot them. Just shot them. After what we saw, we just shot them.”

Some things are better left unsaid.

Carolina told Marcel she was the first in her family to come to France. That she had studied French in school and had read France’s writers and like me had fallen in love with France before ever seeing its shores. She told Marcel about her childhood dreams of coming to France. Carolina also received Marcel’s whiskery kisses, a hug and a declaration of friendship.

The Triumph like any half wild horse demanded attention and respect. Approach it absent-mindedly and try to start it without proper procedure and it would throw you off his back. In a flash you would be flying in the air and landing on your ass in the dirt. I primed the carburetor, swung a leg over, jumped high and came down hard. The engine roared to life, chuffing and thumping, coughing and snorting and promising new roads and far horizons. Marcel and his friend waved to us and called out, “Bon chance,” and we flew away in an envelope of piston roar and fumes.

My scarf got loose and fluttered in the fresh air. Carolina’s arms were around my waist, her hands gripping the belt of my riding jacket, holding on tight to me and to the moment. We drifted south, wandering from highway to byway to country track, past ruined castles and tiny villages unchanged in centuries. The remainder of the day passed in a blissful blur of movement, as free as any day I have ever lived and as clear in memory as if that day were yesterday. We roared up hills and carved clean lines through curves and idled easily over stone bridges, water flowing fast and clear beneath us.

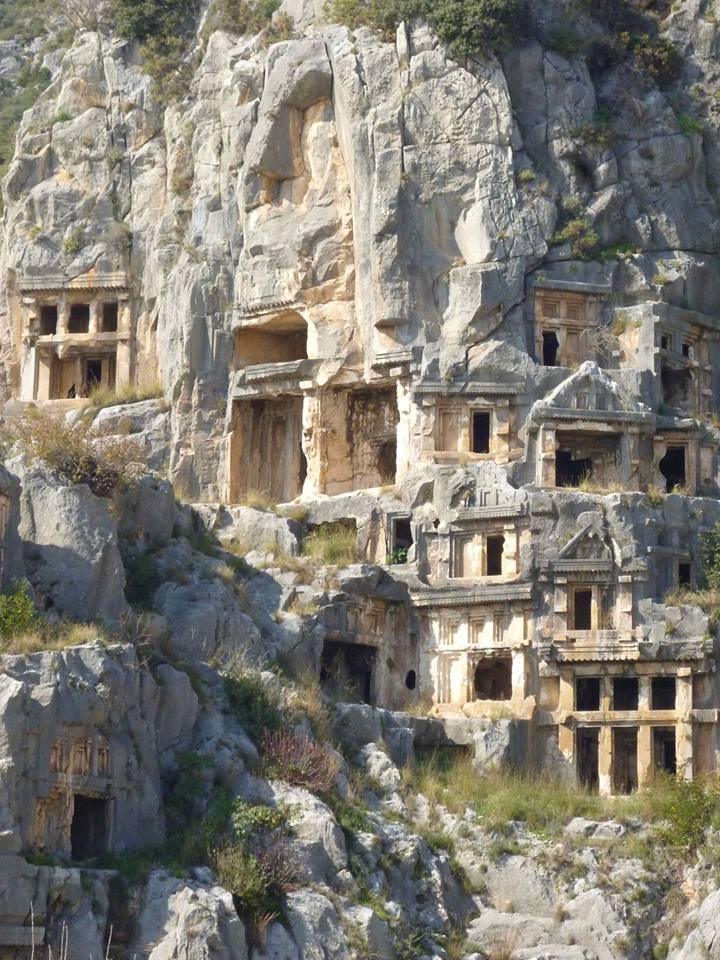

Eventually we found our way into the Dordogne Valley, one of nature’s blessed places. We were awed by the cave paintings at Lascaux and the weight of the millennia separating the artists and ourselves, and by the richness of the valley, its crops and wildflowers bursting with life. One day around noon we stopped at a village general store bordered by stone houses lined along the road. I kicked out the kickstand and went inside in search of lunch, and a corkscrew. The shelves were covered with an assortment of tools and dusty bottles and boxes. There were stacks of the “travail blu” work clothing once seen everywhere in France, baskets of carrots and potatoes, jars of candy, saws, hammers and a hundred other things. A dry ham hung from a hook and ten different cheeses lay in a tray on the counter under a glass cover.

Amid all the clutter I noticed a sinuously curved folding knife with horn scales and a corkscrew on the spine. The horn was smooth and warm in my hand. Looking closely I could see file marks the craftsman had left along the back of the blade. Graceful and elegant the knife embodied craft and consciousness from an earlier time.

A thick chested man with a farmer’s face stomped into the store with mud on his boots. He saw the knife in my hand and congratulated me on my purchase. He took from his pants pocket one similar to mine, but worn with years of use. Henri introduced himself with a farmer’s rough handshake and manner and told me he had a few grapevines nearby and made a small amount of good red wine for the table. Indeed some of it was available on the shelf next to the baskets of eggs. I packed a couple of Henri’s bottles in the Triumph’s saddlebags. A few miles down the road I stopped beside a stream and we made lunch from a few slices of ham, a wedge of Camembert and a baguette.

That night we camped under a two hundred year old oak tree and had Henri’s wine with the remainder of the Camembert and ham and crusty bread. I pulled too hard on the first cork and it popped out spilling a little wine from the green bottle with its hand lettered label. Carolina laughed, and licked the side of the bottle. The wine was smooth and full and tasted of earth and seasons, the color deep red, almost black. We ate slowly, savoring each sip of wine, talking softly, touching each other with hands and eyes. Carolina’s eyes glowed with dark fire and her skin was luminous in the canvas filtered light and her warm and trusting body soon formed to mine. We moved as one, perfectly balanced, two parts of one being, as when riding at speed and pushing our lives to the edge. Everything was soft and perfect and the individual moments all connected to each other to form a long string of perfect moments. We knew this time was marked out from the rest of our lives, that these days and nights were ours to hold close and that they would not ever return.

We continued south over the next week, moving slowly, staying some nights in country hotels and other nights in our tent. The small hotels were rustic, charming and inexpensive, with white walls, thick timbers, sheets stiff from drying in the sun and smelling of grass. But our tent created a transcendent space. Moonlight illuminated the interior of our little hideaway casting a gentle otherworldly radiance over us. Morning sunlight shone green through the canvas roof, warming and awakening us nestled in our cocoon.

Eventually the Triumph swept us over the Pyrenees, across the Spanish border, and… Gone now. Long gone. The tent, the motorcycle – the girl. I lost the girl. I lost her after Spain and after much foolishness. I lost my Carolina through an error of passion, or youth, or plain damn stupidity.

Some days the memories pull hard and a powerful deep running desire for what has passed and will never return rises in my chest and I feel about to explode with memories of the beauty, the perfection, and the pain. Some nights, like this night, I feel the thud of the Triumph’s pistons and smell the green air of our France, Carolina’s and mine. I see Marcel and his wounds, the rivers and fields, and remember the bone deep certainty that the road would never end. And always I remember Carolina and a small green tent pitched under an oak tree at the edge of a friendly farmer’s field where I pulled the cork from a bottle of red red wine and my dark eyed girl laughed and hugged me when the cork made a tiny pop.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

I remember reading this piece in “Passing Through” a few years ago; liked it then, and enjoyed revisiting it. And the there is a joyous note in that Carolina may have disappeared, but the caves, the Dordogne, the crusty bread, the smokey blue Pyrenees. the wildflowers and green air of France is all still here, waiting for you.

and like others I am panting to hear more of Bulgarian odyssey and tales of the Byzantine Empire.

Thanks for your comments Ruthanne. More on Bulgaria soon. Really.